Home / Albums / Tag Place:America 873

Weapons

Weapons Indians of Wisconsin

Indians of Wisconsin The Mound builders

The Mound builders Sitting Bull

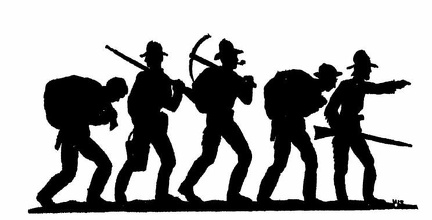

Sitting Bull The Hell-roaring forty-niners

The Hell-roaring forty-niners Musketeer wearing a bandolier

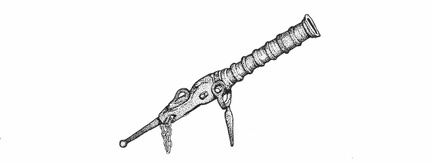

Musketeer wearing a bandolier Patrero

Patrero A seventeenth century musketeer

A seventeenth century musketeer Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe Nathaniel Hawthorne

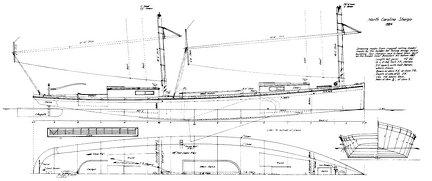

Nathaniel Hawthorne Plan of North Carolina sharpie of the 1880's

Plan of North Carolina sharpie of the 1880's Plan of North Carolina sharpie schooner taken from remains of boat

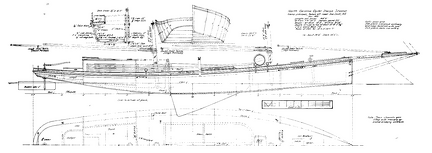

Plan of North Carolina sharpie schooner taken from remains of boat Plan of a Chesapeake Bay terrapin smack

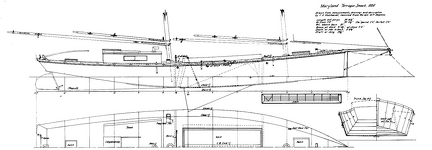

Plan of a Chesapeake Bay terrapin smack Plan of a large Chesapeake Bay sharpie taken from remains of boat

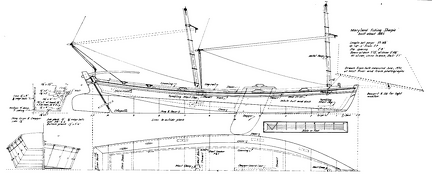

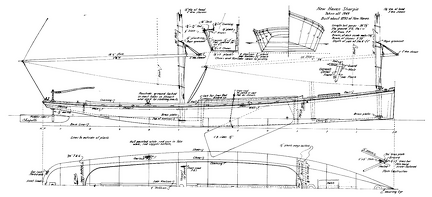

Plan of a large Chesapeake Bay sharpie taken from remains of boat Plan of typical New Haven sharpie showing design and construction characteristics

Plan of typical New Haven sharpie showing design and construction characteristics At Free and Easy Shows

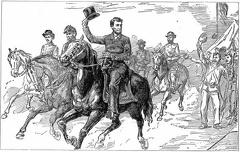

At Free and Easy Shows Lincoln visiting the Army

Lincoln visiting the Army Ford’s Theatre, where President Lincoln was assassinated

Ford’s Theatre, where President Lincoln was assassinated House where the President died

House where the President died Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln The Lincoln Monument, Springfield, Illinois

The Lincoln Monument, Springfield, Illinois Old Monomoy Lighthouse

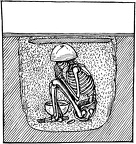

Old Monomoy Lighthouse Urn burial

Urn burial Eleazer Williams

Eleazer Williams Jamestown as it is

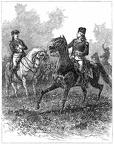

Jamestown as it is Washington rebuking Lee

Washington rebuking Lee On our chieftain speeded, rallied quick the fleeing forces

On our chieftain speeded, rallied quick the fleeing forces Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto Xavier Algara

Xavier Algara Willa Cather

Willa Cather William S Hart

William S Hart W Somerset Maugham

W Somerset Maugham Will Rogers

Will Rogers Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Dreiser Rudolph Valentino

Rudolph Valentino Serge Koussevitsky

Serge Koussevitsky Robert Edmond Jones

Robert Edmond Jones Rose Rolando

Rose Rolando Ralph Barton

Ralph Barton Ramon Del Valle Inclan

Ramon Del Valle Inclan Picasso

Picasso Plutarco Elias Calles

Plutarco Elias Calles Paul Whiteman

Paul Whiteman Pauline Lord

Pauline Lord Mrs. Fiske

Mrs. Fiske Otto H. Kahn

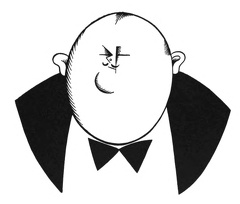

Otto H. Kahn Miguel Covarrubias

Miguel Covarrubias Morris Gest

Morris Gest Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Stokowski Lillian Gish

Lillian Gish Lee Simonson

Lee Simonson Leonore Ulric

Leonore Ulric Jose Juan Tablada

Jose Juan Tablada Joseph Hergesheimer

Joseph Hergesheimer John Barrymore

John Barrymore John D Rockefeller

John D Rockefeller Ivy Maddison

Ivy Maddison Jack Dempsey

Jack Dempsey Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz