Home / Albums / Tag Lighter than Air 20

Glaisher and Coxwell

Glaisher and Coxwell Blanchard’s flying-machine

Blanchard’s flying-machine Charles’ first hydrogen balloon

Charles’ first hydrogen balloon Montgolfier’s experimental balloon

Montgolfier’s experimental balloon Montgolfier’s passenger balloon

Montgolfier’s passenger balloon The Great Balloon of Nassau

The Great Balloon of Nassau Car of Nadar’s balloon

Car of Nadar’s balloon Diagram of a modern spherical balloon with ripping panel

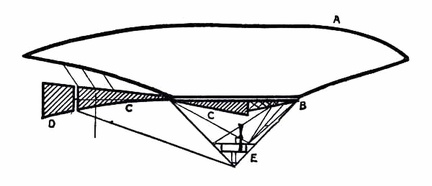

Diagram of a modern spherical balloon with ripping panel Blanchard’s dirigible balloon, 1784

Blanchard’s dirigible balloon, 1784 Robert Brothers’ dirigible, 1784

Robert Brothers’ dirigible, 1784 The car of a modern Balloon

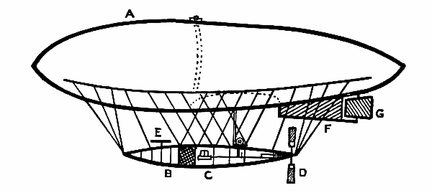

The car of a modern Balloon Semi-rigid Airship

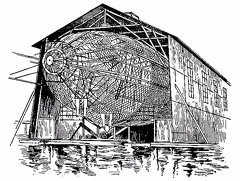

Semi-rigid Airship Hull of a Zeppelin during construction

Hull of a Zeppelin during construction Early-type Airship

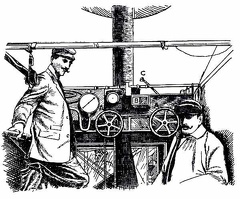

Early-type Airship Control platform of an Airship

Control platform of an Airship A modern Balloon

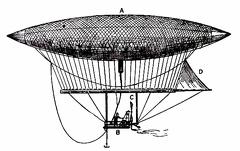

A modern Balloon An Experimental Airship

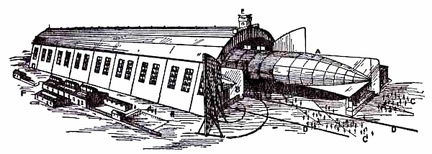

An Experimental Airship An Airship leaving its shed

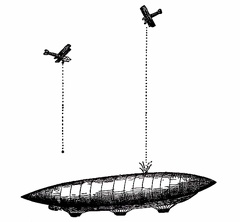

An Airship leaving its shed Aeroplanes attacking an airship from above

Aeroplanes attacking an airship from above The ascension of Montgolfier’s balloon

The ascension of Montgolfier’s balloon