Master of the Year 1446. Christ Nailed to the Cross

Master of the Year 1446. Christ Nailed to the Cross Master of the Playing Cards. Man of Sorrows

Master of the Playing Cards. Man of Sorrows Master of the Playing Cards. St. George

Master of the Playing Cards. St. George He placed the 'drum' on a chair, and practised diligently

He placed the 'drum' on a chair, and practised diligently Charlemagne

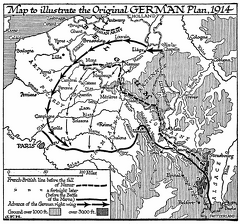

Charlemagne The Original German Plan, 1914

The Original German Plan, 1914 Martin Luther

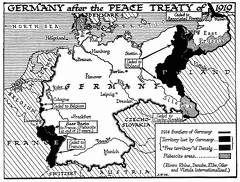

Martin Luther Germany after the Peace Treaty, 1919

Germany after the Peace Treaty, 1919 Emperor William II

Emperor William II Charles V

Charles V Bismarck

Bismarck Costumes of the Franks from the Fourth to the Eighth Centuries

Costumes of the Franks from the Fourth to the Eighth Centuries King or Chief of Franks armed with the Seramasax, from a Miniature of the Ninth Century

King or Chief of Franks armed with the Seramasax, from a Miniature of the Ninth Century